Two decades ago, Nigeria’s pension system was on the brink of collapse. The country was grappling with a debt-ridden, unsustainable pay-as-you-go scheme, where pensioners were often left unpaid for months—if not years. The total liability hovered around ₦2 trillion, with many retirees living in poverty and despair.

That narrative changed dramatically with the enactment of the Pension Reform Act in 2004, which introduced the Contributory Pension Scheme (CPS). The reform ushered in a mandatory, privately managed system where both employees and employers contribute a fixed percentage of monthly earnings toward retirement. It was a game-changer.

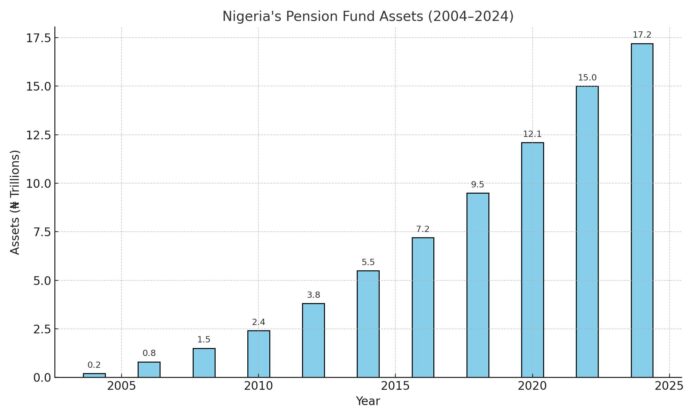

Today, the pension industry has grown into a financial giant, amassing over ₦19 trillion in assets under management. These funds are now one of the most significant pools of long-term capital in Nigeria, financing infrastructure, investing in real estate, supporting government securities, and playing a stabilizing role in the capital markets.

This revolution did not happen overnight. It required strong regulatory oversight by the National Pension Commission (PenCom), the evolution of Pension Fund Administrators (PFAs), and growing trust in the system—especially from workers in the formal sector. It also demanded new thinking about retirement in a country where social safety nets are weak and life expectancy continues to rise.

Yet for all its successes, the CPS still faces important questions. How secure are the pension funds in the face of inflation and currency depreciation? Are PFAs delivering enough returns to outpace the rising cost of living? Why are over 80% of Nigeria’s working population—especially those in the informal sector—not covered?

The structure of the CPS ensures that contributions are invested by licensed PFAs and held in custody by independent Pension Fund Custodians (PFCs). These entities are tightly regulated, but challenges persist. For instance, Nigeria’s double-digit inflation continues to erode the real value of retirement savings. While the nominal asset value of the pension funds has risen dramatically, the purchasing power of retirees remains under pressure.

There is also concern over low coverage. As of early 2025, only about 10 million Nigerians—mostly those employed in the formal sector—are enrolled in the CPS, out of a workforce estimated at over 70 million. This massive gap raises questions about the inclusivity of the system. Efforts have been made to bridge this divide through the Micro Pension Plan, launched in 2019, which targets artisans, traders, and other self-employed Nigerians. But adoption has been slow due to poor awareness, low financial literacy, and trust deficits in financial institutions.

Despite these hurdles, the CPS has recorded some major wins. Retirees under the new scheme now receive benefits more promptly compared to the old defined-benefit model. In addition, the separation of custody and management of funds has reduced fraud risks. The system’s transparency and strong governance framework have earned it praise from international observers.

Still, experts warn that more reform is needed. Many call for inflation-indexed pension products to protect retirees’ income, especially in an economy prone to macroeconomic shocks. Others argue for increased investment in alternative assets—such as agriculture, tech startups, and energy infrastructure—that can yield higher long-term returns while also supporting national development.

PenCom has also been urged to intensify enforcement of compliance among employers, particularly state governments and private companies that fail to remit employee contributions. Furthermore, streamlining pension payout processes and removing bureaucratic bottlenecks will go a long way in improving retiree welfare.

There is also a broader conversation around sustainability. As the population ages and more Nigerians begin to retire, the demand for timely pension payouts will rise. PFAs must adapt by becoming more innovative in fund management and leveraging technology to reach younger and informal-sector workers.

Ultimately, Nigeria’s pension journey is a tale of resilience, innovation, and unrealized potential. From a broken past, the CPS has offered a glimpse of what is possible with the right policies, oversight, and public trust. However, if the country is to unlock the full promise of retirement security for all its citizens, deeper reforms and bold policy action are still required.

The ₦19 trillion fund may be impressive—but the real measure of success will be how many Nigerians it can carry into a dignified retirement.