By NIyi Jacobs

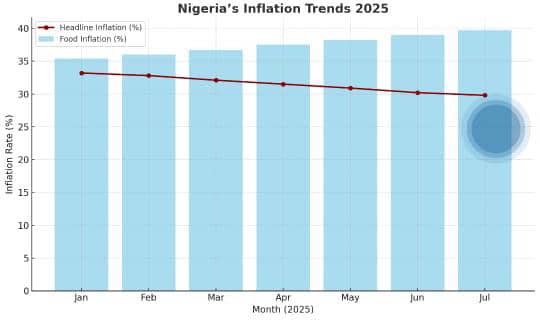

The announcement by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) that headline inflation in Nigeria fell to 21.88 percent in July 2025 from 22.22 percent in June was greeted with optimism by government officials and policy advocates. For many, it was evidence that President Bola Tinubu’s painful reforms—fuel subsidy removal, foreign exchange liberalisation, and tighter monetary policy—were finally beginning to yield results.

The July report marked the fourth consecutive monthly decline in headline inflation since the beginning of the year, a development that technocrats and international observers considered promising. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director-General of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), even praised the administration for restoring a sense of “stability” to the economy.

But walk into any market in Lagos, Kano, or Port Harcourt, and the statistics appear detached from reality. Tomatoes still cost a small fortune, a bag of rice sells for well over N80,000, and transport fares remain stubbornly high. Even the NBS itself admitted that food inflation climbed to 22.74 percent in July, up from 22.67 percent in June, tightening the squeeze on ordinary Nigerians.

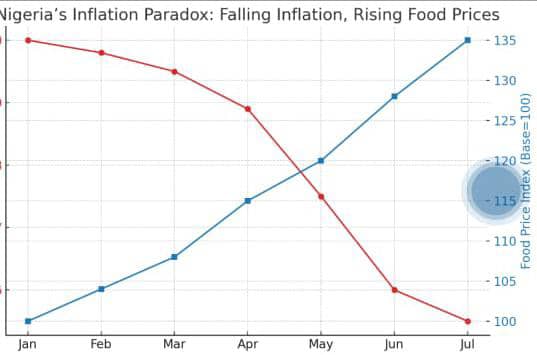

This paradox—falling inflation rates on paper, yet stubbornly rising prices on the ground—is at the heart of Nigeria’s economic dilemma. To understand it, one must unpack what inflation really measures, how it is calculated, and why easing inflation does not equate to lower living costs.

At its core, inflation is not about prices going down—it is about the rate at which they are rising. The key tool economists use to track this is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a basket of goods and services that reflects the cost of living. The NBS calculates CPI changes by tracking hundreds of items across food, housing, transport, clothing, healthcare, and education.

When the bureau reported 21.88 percent inflation in July, it meant that, on average, goods and services were 21.88 percent more expensive than they were in July 2024. For example, if a tuber of yam cost N500 last year, it now costs roughly N609. This does not mean yam is cheaper—it simply means it is rising at a slower pace compared to earlier spikes.

The NBS also tracks month-on-month inflation, which compares prices from one month to the next. In July, month-on-month inflation rose to 1.99 percent, up from 1.88 percent in June. This means that between June and July alone, the CPI basket became nearly 2 percent more expensive. In simple terms, while annual inflation is decelerating, short-term pressures remain strong. That is why consumers feel little or no relief at the market.

The contradiction between statistics and experience is most stark in food prices. Food accounts for over 50 percent of household spending in Nigeria, making it the most consequential driver of inflation. The NBS July report confirmed this, showing food inflation climbing even as headline inflation eased. Items such as yam, beans, rice, tomatoes, and palm oil have all seen relentless price hikes.

A telling illustration comes from the Jollof Index, a quarterly report by SBM Intelligence. It tracks the cost of cooking a pot of Nigeria’s beloved jollof rice across the country. Between March 2023 and June 2025, the average cost rose by 153 percent, reaching N27,528. In some states, cooking a pot of jollof rice now consumes nearly 40 percent of the new minimum wage, meaning even basic cultural staples are slipping out of reach. For families, the numbers are not abstract—they are dinner tables without food.

The core reason prices do not fall even when inflation eases is that inflation measures the speed of price increases, not the level of prices. Once prices rise, they rarely fall back to their original levels, unless driven by extraordinary circumstances such as subsidies, currency appreciation, or bumper harvests. Consider this: if a bag of rice costs N50,000 today and inflation is running at 30 percent, the price could climb to N65,000 within a year. If inflation later slows to 15 percent, the bag could still rise to N74,750 the following year. Prices are still going up—just not as sharply. This explains why Nigerians see no immediate relief even when the government celebrates “disinflation.” Lower inflation does not mean cheaper food or transport; it means prices are increasing at a reduced pace.

Another wrinkle in the inflation story came in January 2025, when the NBS rebased the CPI, updating the base year and expanding the items in the basket. Overnight, headline inflation dropped from 34.8 percent in December 2024 to 24.48 percent in January. While rebasing is a standard statistical practice globally, critics argue that it often masks the lived experience of citizens. In Nigeria, the rebasing helped align data with international standards, but it also created the impression that inflation had sharply eased, even though market realities remained unchanged. This statistical adjustment illustrates how technical changes can influence perceptions without altering ground-level realities.

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has also maintained a tight monetary stance, holding interest rates at 27.5 percent. The logic is straightforward: higher rates discourage borrowing, reduce spending, and curb demand-driven inflation. For large corporations considering expansion, or for investors weighing risks, this sends a signal that Nigeria is serious about stabilising its economy. However, monetary policy is a blunt instrument that does little to address food inflation, which is largely driven by supply-side issues—poor infrastructure, insecurity in farming communities, high transport costs, and climate disruptions. Thus, while the CBN’s hawkish stance may help stabilise the naira and reduce speculative attacks, it does little to lower the cost of beans or palm oil in the market. In fact, high interest rates often raise production costs for businesses, who then pass them on to consumers.

When Okonjo-Iweala spoke of stability, she was speaking in technical terms. Stability, in the language of economists, means reduced volatility—no sudden currency crashes, no runaway inflation, no fiscal chaos. From this perspective, Nigeria has indeed become more stable. The naira is not spiralling as fast as in 2023, foreign reserves are climbing, and inflation is easing. Investors prefer such predictability, even if growth remains modest.

But stability is not the same as affordability. A more predictable inflation path may please international markets, but Nigerians still measure stability by whether they can afford garri, fuel, and school fees. For the woman in Mile 12 market, stability without affordability feels like a hollow victory.

Economists call the current phase disinflation—a slowdown in the pace of inflation. But for ordinary Nigerians, disinflation without falling prices feels indistinguishable from inflation itself. This disconnect highlights the limits of economic statistics in capturing lived experiences. It also underscores why government must be careful in celebrating headline figures without addressing root causes. Nigerians want cheaper food, reliable power, affordable transport, and secure jobs—not just technical progress reports.

Nigeria’s inflation problem is complex and cannot be solved by monetary policy alone. It requires a broader strategy that addresses food production, transport bottlenecks, and the cost of doing business. Boosting agricultural productivity is central: insecurity in farming areas must be addressed, rural roads improved, and access to affordable fertilisers and mechanisation expanded. Transport infrastructure also needs urgent investment in rail, ports, and logistics to reduce costs passed on to consumers.

At the same time, small businesses, which form the backbone of Nigeria’s economy, need relief from high borrowing costs. Without targeted interventions, firms will continue to transfer credit expenses to customers. Direct support for vulnerable households through stronger social safety nets is also essential to cushion immediate pains. And finally, policymakers must improve data transparency and explain inflation trends in plain language, bridging the gap between statistical disinflation and daily struggles.

Nigeria’s inflation numbers may be easing, but prices remain painfully high. The paradox reflects the difference between statistical disinflation and economic relief. While international institutions may see stability, Nigerians measure success by what they can afford at the market. Until food prices fall or incomes rise meaningfully, falling inflation rates will remain an abstract achievement, celebrated in press releases but questioned in the streets. The government must therefore move beyond technical stability to tangible affordability. Only then will declining inflation translate into a better life for Nigerians.